Leading change is probably the main task of leaders today. The environment in which we operate is disrupted, turbulent and ever-accelerating. To survive and remain relevant NGOs and even churches have to change at a faster pace than ever before. Change really is the only constant for leaders today.

Researchers estimate that around 75% of organizational change efforts fail. Few NGO and church leaders are trained or experienced to manage change. We would do well to take the advice of Marcus Aurelius, who 2000 years ago suggested:

Make a habit of regularly observing the universal process of change: be assiduous in your attention to it and school yourself thoroughly in this branch of study: there is nothing more elevating to the mind.

To understand change, we first need to debunk two appealing, but deeply misguided, assumptions about change.

- The first myth is that organizations behave like logical machines. They do not. Organizations are full of complex entities called human beings. So for an organization to change, people have to change how they behave. We all know from personal experience that changing behavior is far harder and more complicated than it sounds.

- The second myth is that we can actually control change. Organizations operate in open systems in rapidly changing environments. Leading in the context of change is more like paddling in permanent white water than a placid lake. As leaders we can only disturb a system, but we cannot manage and predict how it will respond.

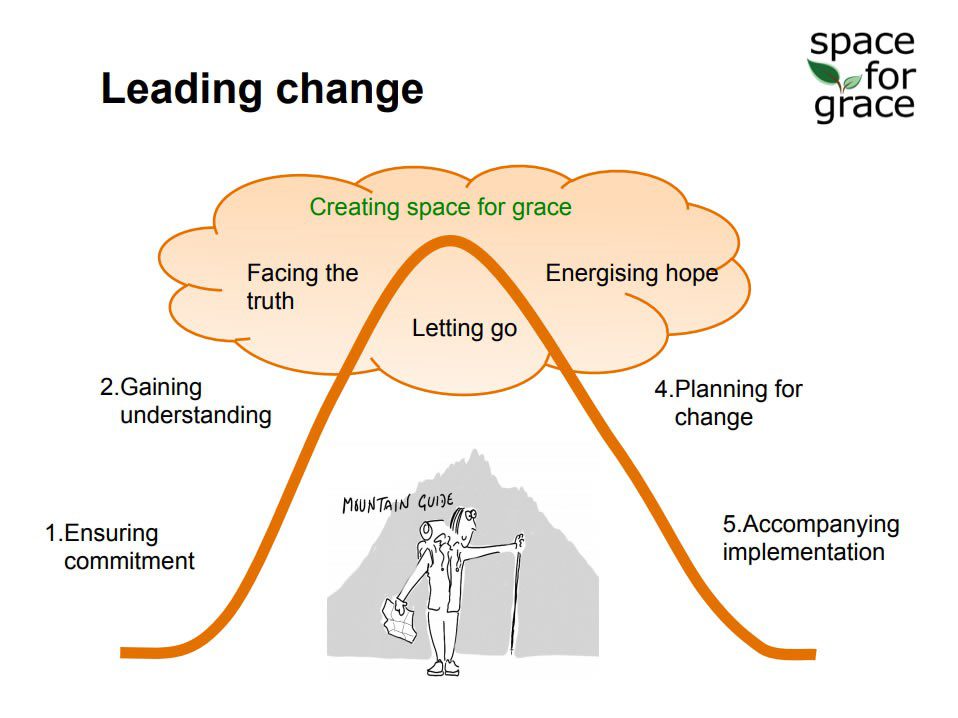

But in such a complex task of leading change, we need some models to shed some light. My own 30 years’ experience meddling in change process with NGOs has made me see change a bit like climbing up and down a mountain through key stages along the way. This mountain model of change clearly over-simplifies reality. The phases are not as linear as they appear here: they merge, flow together, zigzag, overlap and iterate. They do not have to follow this idealized sequence. Organizations probably never arrive neatly at the end point. After all, change is constant. So going through this model is not a one-off event, but a continual re-creation.

Stage 1: Ensuring commitment

For any organization or individual to change, they need the motive – the will to change. Unless people feel that the current situation cannot go on and that they have to move fast, they will tend to stick with what they know. Most organizations change as little as they have to. So at the outset there must be a strong enough motive for change both from leadership and from a critical mass of staff to overcome the natural resistance.

In leading change, it is important to assess who really wants change. What do the senior staff think? What is the board appetite for change? Why do they want change? And how much do they want it?

Meaningful change is costly. It is not simply about learning new skills and acquiring new knowledge. It also involves giving up bad habits and behaving in new ways. It sometimes means admitting you were wrong. Change is often painful, sensitive and personal. We often only think it’s others who need to change. But leading change is not really about changing other people’s behavior. After all, who is the only person you can change? It’s you!

So in leading change, our biggest question is: Are we really up for it? Are we genuinely prepared to change ourselves? The experienced consultant Robert Quinn says:

When I discuss the leadership of organizational change with executives, I usually go to the place they least expect. The bottom line is that they cannot change the organization unless they first change themselves.

My doctorate research with NGOs in Africa concluded the same ‒ that leadership commitment to organizational change is synonymous with their commitment to their own personal change.

A few years ago some European funders asked me to help one of their church partners in Zimbabwe. They said: “This organization is a disaster. They have been silent in the face of human rights abuses and are politically compromised. They are corrupt. They have lost credibility among their members and funding from donors. They need radical change. Can you help?” Despite the obvious challenge, I was so excited by the prospect of contributing at such an important time. So I eagerly asked them: “So what does the general secretary and the board think about the need for change?” They replied, “Oh, they are completely against it. In fact, they are the root of the problem as they are in the pay of the State President.” But without leadership openness to change, there is nothing anyone can do. With great reluctance I felt I had to turn down the opportunity. The happy ending is that two years later with a new board in place, the partner asked me again to get involved – and it turned out to be an amazing transformational experience.

Stage 2: Gaining understanding

To assist any organization to change, including our own, we need to understand what really makes it behave as it does. We need to appreciate the influences from the wider system in which it operates. No church or NGO is an island. It operates in a complex network of relationships with stakeholders, including funders, government, and community groups.

We need to work out what is really going on and try and see beyond what is visible on the surface. We need to look below the waterline to discern the root causes of the underlying attitudes that make it behave as it does.

But coming to such conclusions ourselves is the easy part. If we are to get people within the organization to change, they have to own it themselves. They have to do their own self-diagnosis and identify what needs to change. If people do not own the need for change, their commitment will be lukewarm at best, if not indeed resistant. So as a leader you may have to withhold your own diagnosis in order to allow people to reach their own conclusions.

A tempting short-cut

Once people have identified the core issues, there’s a strong temptation to move directly from diagnosis to planning. It keeps everything at a safe, rational, cerebral level. But taking this short-cut misses out the all-important summit of change. The summit is the turning point, where the emotional and even spiritual elements catalyze human change. It’s emotion, not brute logic that drives and fuels people to change how they behave. Without reaching the summit, our efforts at change remain quite superficial – more like most New Year resolutions.

Stage 3: Inspiring change

Reaching the summit is not easy, nor much fun. It is often the steepest and potentially the most dangerous part of the journey. It may be cold and foggy, hard to see the way ahead. People are usually tired and complaining. It’s an emotional place. My colleague, Bill Crooks, calls it the “groan zone.” At the summit we help the organization do three things: face the truth; let go of past ways of working; and energize hope for change.

Facing the truth

Truthful feedback given in the appropriate way is a vital ingredient in any change. In fact, truth is the trigger. The psychologist John White points out: “No-one ever really changes for the better without somehow facing the truth.” For people and organizations to change, they have to acknowledge there are areas for improvement. Change is often about helping people and organizations become aware of their blind spots.

Feedback that catalyzes change is so much more complex than simply telling another person what to do or how they have failed. How we give feedback, where, when and in what tone are just as important as the content of what we say. People change when they feel accepted and secure – not attacked. So it’s vital to create a safe space where people feel valued and affirmed and therefore open to hearing feedback. Sometimes simply asking penetrating questions can powerful. But even more effective is letting people’s own consciences do the work.

I learned this lesson a number of years ago. I’d been asked to facilitate a strategy workshop with an umbrella body. In reality, it was the final roll of the dice as this network was the sickest, most corrupt organization I had ever come across. The Chair and Vice Chair were being bribed by the State President. Members had burned down each other’s buildings the week before I arrived. I was threatened with deportation if the workshop did not go well. I only found out later that I’d been selected, not for my skill as a consultant, but because they mistakenly believed I would not be intimidated by threat of prison.

On the second day everything changed when after a reading of Scripture, I suddenly had 40 faith leaders on their knees at the front of the room wailing for the mess the organization was in. It was a powerful group process, but I felt people needed to take personal responsibility. So I sent them off on their own to listen to God and answer the simple question, “How have I contributed to this situation?” They then got together in small groups to tell each other what they felt they heard. Everything came out – about how they had prostituted themselves before the President. It proved to be a transformational moment. It brought radical and lasting change. After 15 years, the organization is thriving today.

Letting go

As people face the truth, they need to let go of past ways of thinking and behaving. People cannot be forced to change from the outside. It has to come from within. This stage often involves helping people to surface their fears, face them and take personal responsibility for their contribution to the situation. Leaders often have to go first. It usually involves an apology. It’s so tempting to skip past this painful stage. Yet, without it, there is no turning point.

William Bridges wrote back in 1995 … “The failure to identify and be ready for the endings and losses that change involves is the largest single problem that organizations in transition encounter.”

If this letting go is like breathing out – expelling carbon dioxide ‒ then receiving hope and energy for change is like breathing in oxygen.

Energizing hope

Change is not just doom and gloom, it is also hopeful and exciting. Change is about taking new opportunities. It is about discerning the way forward. At the summit of change, there is an injection of energy – a relief at letting go of burdens and a realization that change is possible. We may get inspiring views into the future. People begin to open themselves up to change. They start reconciling relationships and rebuilding trust. This often involves forgiving each other. Again leaders have to model the way! It is about creating and holding this emotional, and even spiritual space. It is about creating space for grace.

There is a positive injection of energy at the turning point – a relief at letting go of burdens and hope and excitement that change is actually possible. There is a vision for change.

Hope is a vital ingredient for any change. As Gervase Bushe says:

It is impossible to get people to collectively act to change the future if they don’t have hope. To some extent hope is born out of discovering that we share common images of a better team, organization or world.

Stage 4: Planning for implementation

Finally we’re on our way down the mountain – though coming down may feel as hard on the knees as the climb up! We now need to productively channel this excitement and energy by planning collaboratively for change.

This stage is all about working out the practicalities: What is the change we want to see? What does it look like? What needs to be done? By whom? And when? How will we know if we have arrived?

It’s tempting in this planning stage to abdicate responsibility for change to one or two people – “Phew … the rest of us go back and get on with our normal jobs.” But if only a few people are involved, then little change may actually take place. It’s about getting people to take collective responsibility for change.

Walter Wright goes as far as to say,

We do not have a plan until each objective has been owned by someone who accepts responsibility to see that it is initiated and completed.

An internal task force (or guiding team, change action team or steering group) can help oversee the process. They can keep the energy for change alive, reminding people of their responsibilities and deadlines. But it still needs you as a leader to show this change remains a top priority.

It also needs you as a leader to show empathy and sensitivity with the human cost of change. Adjusting to new ways of working may be difficult for some people. It may be that they have to go through transition stages of denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance, similar to the process of coming to terms with grief that Elisabeth Kübler Ross so eloquently describes.

Stage 5: Accompanying implementation

We sometimes fall into the trap of thinking that we have arrived once we reach the planning stage. But the real work of implementing change is only just beginning. This is where change becomes embedded (or not).

It’s the leader’s role to keep up the momentum for change. Regular monitoring, constantly

asking, “How are things going?” can maintain energy and build commitment, as

people realize they are making progress. We all want to join in with something

that is moving in the right direction. So it’s important to monitor what has already

changed and celebrate those successes along the way.

As leaders, we may benefit from outside support to accompany this implementation. Consultants can help provide some external accountability. They may also be able to provide us with one-to-one coaching support to assist us make our own necessary changes. They can ask us the right questions that no one else dares to. They can also provide us with a safe place to vent our concerns and regain a bit of perspective about what is going on.

Leader as mountain guide

You as a leader may be a bit like a guide helping your own organization up and down this mountain of change. How effective you are as a guide, once again comes down to how much people trust you. Are they prepared to follow you – even when it is difficult to see the way ahead? When they are tired and frustrated and longing for an easier life?

If we dare to intervene in other peoples’ lives we have to bring the best of ourselves to a really challenging role. We need the self-awareness to know ourselves, the power, the strengths and the biases we bring, as well as the temptations we face. We should set ourselves high standards and commit ourselves to continuous learning. We need the self-discipline to manage ourselves and our time to ensure we are as spiritually, mentally, and emotionally as fit as possible. As we cultivate virtues of compassion, patience, honesty and determination, people trust us more and our effectiveness as change agents increases. To inspire change we need both courage and humility.

Rick James

Rick James